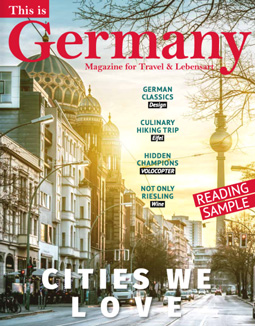

Berlin Landmarks

By any European capital’s standards, Berlin has been through a lot — and its fractured and fascinating history is reflected in the diversity of its architecture, which ranges from neoclassical and renaissance-era buildings through to ideological remnants from former fascist and communist regimes; and plenty of post-modernism too.

Amongst the myriad monasteries, churches, factories, schools, breweries and skyscrapers that dot the city today, visitors can encounter works by world-famous architects that span centuries: Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Andreas Schlüter, Peter Behrens, Walter Gropius, Frank Gehry and Norman Foster are just some of the big names who have left their mark on the German capital.

Below are some of our favourite city landmarks, plucked from various eras.

By Paul Sullivan

Nikolaikirche

The distinctive green spires that rise from the medieval Nikolaiviertel belong to the quarter’s eponymous 13th century church: the Nikolaikirche. Completed in 1230, orginally in late-Romanesque style, it has been a city landmark for over eight centuries. Most of it has been rebuilt over that time, hence its current mix of Gothic and Baroque elements, though one of the crypts is considered the oldest room in Berlin. A permanent exhibition inside offers visitors insights into the history of the church and the surrounding area, and hosts events, concerts, services and more.

Deutches Historisches Museum (German History Museum)

There are two distinctive architectural elements to Berlin’s vast German History Museum. The main Baroque building — the oldest on Unter den Linden — was designed as an armoury (Zeughaus) by Johann Arnold Nering in 1695, and today houses 2000 years of German history. It’s a striking structure, with some excellent attention to detail like the series of ‚masks’ of dying giants that sit above the arched windows of the courtyard, crafted by sculptor and architect Andreas Schlüter. Behind the main building sits a contrastively new, glass-heavy exhibition space, built by Chinese-American architect I M Pei in 2003, which is used for temporary exhibitions.

Ephraim Palais

There are not too many examples of Rococo architecture in Berlin, but this stately building — originally constructed between 1762-1766 but rebuilt in the 1980s with original elements that were thankfully saved and stored in East Germany — is one of the finest examples. Built in the 1760s by architect Friedrich Wilhelm Diterichs for court jeweller and coin maker Veitel Heine Ephraim, its façade, decorated with ornate golden balconies, is immediately eye-catching when strolling around the Nikolaiviertel. Inside you can find exhibitions about Berlin’s cultural history as well as the building’s original spiral staircase, and a beautifully decorated ceiling (first floor) by Andreas Schlüter.

Altes Museum

Karl Friedrich Schinkel is one of the most significant names in Berlin architecture, with several major early- to mid-19th century buildings — the Neue Wache and the Konzerthaus included — tracing his signature neoclassical style. One of his most prominent structures is the city’s first ever museum, the Altes Museum (1823-1830), whose wide, Greek-inspired façade, with its 18 fluted ionic columns and grand staircase, sits proudly opposite the Royal Palace, and right next to the Berlin Cathedral — both of which Schinkel also worked on. Originally built to house all of Berlin’s royal art collections, the Altes Museum has held the Collection of Classical Antiquities since 1904; inside, visitors can also find a spacious atrium, attractive rotunda and grand staircase.

smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/altes-museum/home/

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church

Designed by royal architect Franz Schwechten and constructed in the 1890s as a memorial to Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm I, this eye-catching church in west Berlin is today mostly famous for its partially destroyed tower — known as the ‘chipped tooth’ by locals — which was aerial bombed during World War Two and left as a memorial to peace and reconciliation. The rest of the damaged church was rebuilt in the 1960s by architect and designer Egon Eiermann, who added contemporary elements such as an octagonal nave with 20,000 blue glass panels; these glow beautifully at night and lend the structure an almost futuristic sci-fi feel. The interior of the main church hosts a museum and also holds services.

gedaechtniskirche-berlin.de/page/1611/information-visitors-where-find-us

Rotes Rathaus

Sitting on the cleared or buried remains of several previous town halls — built from the 14th century onwards — this latest incarnation is so-named for its distinctive use of traditional red clinker bricks. The monumental three-story structure, located near Alexanderplatz, literally can’t be missed, since it occupies an entire city block. Built between 1861 and 1869 in Italian high Renaissance style by architect Hermann Friedrich Waesemann, it was destroyed in the war but rebuilt between 1951-1958. Its 74-meter tower has a tower, modelled on the cathedral of Laon, that has wonderful views if you’re willing to climb the spiral staircase to get there.

visitberlin.de/en/berlin-city-hall

Reichstag

One of Berlin’s most famous buildings, the neo-Baroque Reichstag squats close to the another iconic landmark, the Brandenburg Gate, both of them adjacent to the city’s leafy Tiergarten. The original 19th building was designed by Paul Wallot as an ode to Imperial might. Damaged by a mysterious fire in 1933 (which famously allowed Hitler to impose non-democratic emergency decrees), then attacked by air raids and Red Army shelling during World War Two, its interior decoration was stripped out by Paul Baumgarten in the 1960s, and it was given a broader makeover in the 1990s by Norman Foster. It was Foster who installed the building’s most conspicuous feature, its spectacular glass dome, which offers panoramic views over the government quarter and beyond.

bundestag.de/en/visittheBundestag/dome/registration-245686

Olympic Stadium

Built to a design by Werner March, this stadium is one of the primary existing examples of Nazi architecture in Berlin. In keeping with the fascist regime’s obsession with monumental buildings, the vast structure was expanded from a previous design (also by March), for the occasion of the 1936 Olympic Summer Games — which famously didn’t go according to plan thanks to the superior athletic prowess of Jesse Owens. These days the stadium has a modern roof and other contemporary technological aspects, but many buildings and elements — including the former Olympic swimming pools, ticket offices, Neoclassical colonnade, and Maifeld sports ground — are listed historical monuments and can be accessed via a tour (guided and non-guided available).

Fernsehturm (TV Tower)

Berlin’s television tower is one of its most recognisable structures, adorning everything from teeshirts to official city promotional material, and also serves as a particularly helpful navigation tool for anyone lost in the city thanks to its 368-metre height. Partly designed by well-known architect Hermann Henselmann and located right next to Alexanderplatz, it was one of the most conspicuous building projects of the GDR (East German regime), and as such is also a reminder of Berlin’s former status as a divided city—and of an entire country that disappeared from sight in 1989. Today the tower has viewing platform, rotating restaurant and gift shop.

Haus der Kulturen der Welt

Originally built as the West Berlin Congress Hall, this unique building hugs the Spree on the periphery of the Tiergarten and was designed by American architect Hugh Stubbins in the 1950s. Its playful curves were designed to purposefully contrast with the austere Communist architecture on the other side of the Berlin Wall at the time. Nowadays it houses a committed cultural space that explores the artistic and intellectual relationship between Berlin and the rest of the world. Look out too for the bronze statue — Large Divided Oval: Butterfly — outside the building, which sits in a pond and is Henry Moore’s final major work.

Potsdamer Platz 1

The cluster of prestigious starchitect skyscrapers built on Potsdamer Platz during the 90s were intended as a symbol of reunification and Berlin’s re-establishment as the corporate capital of Germany. These days many visitors find the area quite soulless, but there’s no denying the looming eye-candy on offer, from the glistening chrome-and-steel Sony Centre to Renzo Piano’s distinctive experiments. One of the most handsome buildings is the simply named Potsdamer Platz 1, a 103-metre tall tower of peat-fired brick designed by Hans Kollhoff. Reminiscent of 1920s U.S. skyscrapers, it’s a popular spot for tourists thank to an observation deck and panoramic café located on the top floors and accessed via a very fast elevator.

Photos: iStock